Q&A with Artist Arlie Hammons

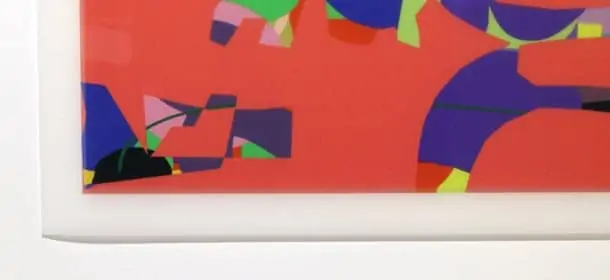

Arlie Hammons won the Marshall Award for best-in-show with his print, Klafangled #4, in the April “Pop Art” exhibit (open through May 5). We asked him when he knew he wanted to be an artist.

“I never wanted to be an artist,” he said. “I was dragged into it.”

Many Art League artists are people who have come to art later in life — as a career change, after retirement, or just picking it back up after a while. Hammons’ reason is different: he experienced a traumatic brain injury.

Before his injury, Hammons worked in IT. After his injury, he was first introduced to art by Marcia Dullum, an Art League and Torpedo Factory artist.

They met at a picnic in 2006, and when Hammons learned Dullum was an artist, he expressed an interest in finding out what he could do artistically — specifically, with graphic design, Dullum said.

They became art friends. He enrolled in a graphic design course at The Art League. Before he had a studio, he and Dullum would paint together in his garage.

Since then, he’s studied art with teachers including Marsha Staiger at The Art League and Mira Hecht at the Corcoran, and moved from graphic design into abstract art, while incorporating his background in computers.

“The way I see Arlie today … he’s kind of come back, full circle, to this place that he can use his expertise,” Dullum said. “When I see that piece down there (in The Art League Gallery), I see the full circle.”

This piece, and the series it’s part of, has its origins about three years ago, when Hammons wrote a computer program to generate random images. Those images form the basis for paintings, or in this case, mylar prints. Hammons describes it in his artist statement:

“My paintings grow from within the confines of a computer screen. A programmatic computer image — random and non-repeatable — is created by a computer program that I write and at times modify. This image is masked out using free-hand drawing with a mouse and graphics software. The resulting image is hand-traced to create a vector image. These drawings are drastically enlarged and either digitally printed directly onto mylar using UV-cured ink, or hand-painted on canvas using synthetic polymers.”

The main factor in deciding between a painting and a print is “how much time I have,” Hammons said. When he paints a piece, he’ll change a color if he doesn’t like it. With a print, he uses the colors as they come.

Hammons’ main motivation comes from a desire to experiment and make new things. The computer program came about because “I wanted to see shapes and things I hadn’t seen before,” Hammons said.

To print his images, Hammons wanted Mylar and the waxy look it creates, he said. Printing on Mylar presents its own challenges, which he worked out by talking to a printer.

After creating four series from his computer program, Hammons’ experimental energy and interest in randomness are currently leading him in a new direction: he wants to use a taffy pulling machine to make art. At the moment, he’s not sharing what that will look like, other than to say it will be more 3-D than 2-D. Like his computer, a taffy pulling machine would inject an element of chaos into Hammons’ artwork.

Dullum said she’s grateful that the juror recognized this body of work, and touched that Hammons credits her with starting him on the path to being an artist.

“But he did the work of learning to be an artist,” she said — work that includes large parts of rejection and showing up. Dullum said she hopes Hammons continues down the path he’s on.

“In art, you never find yourself. It’s a continual journey.”

Can't get enough?

Sign up for our weekly blog newsletter, subscribe to our RSS feed, or like us on Facebook for the latest Art League news. Visit our homepage for more information about our classes, exhibits, and events in Old Town Alexandria, Virginia.